Visitors from Australia to Argentina shuffle the two miles between the Auschwitz and Birkenau concentration camps at the 2024 March of the Living (MOTL) in Poland in a solemn yet empowering ritual to preserve the lessons of the Holocaust. New Jersey State Troopers Mudduser Malik and Marc Zislin, in full police regalia, are among them.

No one confronts them complaining about police overzealousness or indifference. There is no contempt or judgment. No one even teases them by asking what exit in New Jersey they live at.

They encounter only respect, gratitude and wonder.

The marchers don’t know that the troopers — one Muslim, one Jewish — are fast friends and are walking in solidarity to model camaraderie and respect during a painfully difficult time that has divided their communities.

In fact, they, along with the rest of their contingent of law enforcement officials from across the United States and Canada — spearheaded by Paul Goldenberg of the Miller Center for Policing and Community Resilience at Rutgers and the Global Consortium of Law Enforcement Training Executives (GCLETE) — are treated like heroes.

Participants from around the world pick through the crowd to acknowledge and chat with them. Many pull them aside for selfies. New Jersey residents recognize Colonel Patrick Callahan of the New Jersey State Police from the year before and salute him. Marchers from Brazil, Lithuania, Panama and Los Angeles shout greetings in various languages. An animated teenager from Brussels named Leo asks to try on St. Charles (Louisiana) Sheriff Greg Champagne’s hat. The sheriff cheerfully complies, and they pose for a photo together.

Many in our delegation marvel at the number of young people in the crowd. Royal Canadian Mounted Police (RCMP) Assistant Commissioner Brigitte Gauvin notes the significance of youth connecting with a historical event in the age of millisecond attention spans and short memories. “The more they know about history, the better the chance we have that history won’t repeat itself,” she says. Below, delegation members stand under the main entry gate at Auschwitz I, the official starting point of the March of the Living. The inscription, “Arbeit Macht Frei,” is German for “Work Sets You Free.”

The tableau could hardly be starker than 80 years earlier, when law enforcement was complicit in the Holocaust and police uniforms meant grave danger. In the 1930s, police all over the continent fell under the spell of Nazism, social and career pressure, and the temptation to scapegoat the “other.”

A renewed mission

Last year, Goldenberg marshaled almost two dozen police officials from across Europe and North America to join the March and acknowledge law enforcement’s role in the Holocaust, where they vowed to operationalize the phrase “Never again” by creating specialized training. (Police1 documented the event in an article.)

Goldenberg, the nation’s first chief of a state hate crimes division and a veteran police executive in New Jersey, knew that this year’s mission required a delicate approach after the Hamas attacks on October 7, 2023. Intervening world events have radically changed the tenor of the March. Last year’s version, while of course suffused with sorrow, conveyed hope. The events of October 7 and beyond have transformed most of that hope into dread and foreboding.

Selecting the right participants would be critical. Troopers Malik and Zislin, as well as the other executives, embodied the remaining hope.

The group watches Holocaust survivors, who once took the stage to talk about an experience from decades earlier and warn about the horror that can ensue from unbridled hate, instead share fresh scars. Survivors, who had navigated indelible trauma for 80 years, speak in cracking voices and between sobs of grandchildren kidnapped, friends and neighbors murdered, and their sense of sanctuary in the one place they are comfortable being Jewish — demolished.

It becomes clear that our delegation, part of the metaphorical thin blue line that protects civilized society from the worst elements of human nature, now represents the fragile barrier between “Never again” and “Not again.”

The new abnormal?

The defund movement and public hostility have marginalized, and in some cases dehumanized, the U.S. law enforcement community. Hostility against police has become the new norm. Record numbers of law enforcement officers are taking early retirement and switching careers. Recruitment numbers are down, insufficient to counterbalance the exodus. Inestimable experience, expertise, and relationships are vanishing.

“In the United States, our police feel under attack,” warns Goldenberg. “Extremists have eroded the police psyche,” he adds, and politicians score easy points by blaming law enforcement for social ills.

“We use police and emergency services like a light switch,” Goldenberg explains. “Flick the switch and the response is immediate. With today’s erosion of both manpower and spirit, however, that level of services is at risk. “The greatest threat to democracy is the day an average citizen calls 911 and no one is left to respond.”

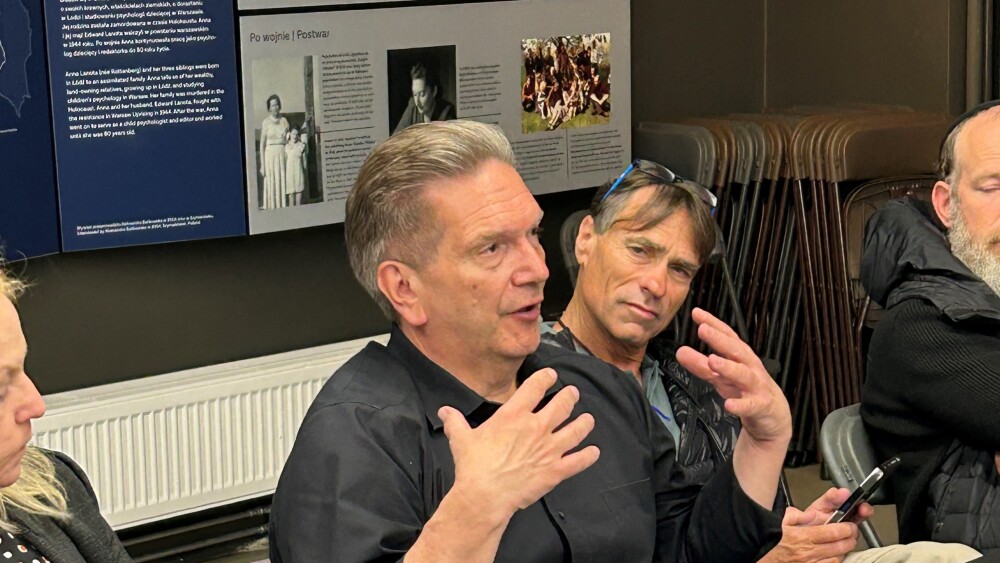

Paul Goldenberg speaking with NJSP representatives outside of the barracks in Auschwitz. L-R: Colonel Patrick Callahan – Superintendent, New Jersey State Police, Paul Goldenberg, Trooper I Mudduser Malik - New Jersey State Police, SGT 1st Class Marc Zislin, New Jersey State Police.

Photo/Mark Genatempo

A reckoning for campus police

October 7 also ushered in a new world for police at colleges and universities. Campus law enforcement once seemed immune to the kind of scrutiny received by state and municipal police. While they deal with the same range of incidents as any sworn police force, they were often perceived as surrogate parents or caregivers, dispensing advice and warnings rather than making arrests.

After the Hamas attack on Israel and Israel’s retaliation in Gaza, however, campuses became centers for protest that have flared into antisemitism, threats and violence. As pro-Gaza encampments popped up at more than 200 universities, campus police have found themselves at the center of a political conflagration under the scrutiny of administrators, students, faculty, the media, civil libertarians and others. They are understaffed, under resourced and subject to the political whims of many masters — presidents, deans, chancellors, administrators and boards.

Meantime, students supporting Israel have faced threats, abuse, antisemitism and violence. Chief Paul M. Cell (ret.), executive director of the International Association of Campus Law Enforcement Administrators (IACLEA) and a prominent member of this year’s MOTL delegation, notes that more than half the protesters are outsiders “being paid to come in and start problems.” The situation got so bad at Columbia that a rabbi advised Jewish students to go home for the rest of the semester.

Cell, whose organization is a leading authority on campus policing and public safety, describes how campus law enforcement executives have been caught in a political whipsaw. At some universities, the administration permitted pro-Gaza encampments despite recommendations to do otherwise from campus law enforcement. After these encampments grew and attracted outside supporters, opponents and the media, administrators asked campus police to help remove the installations — with the result that their department’s handful of officers had no chance to succeed, or even keep the peace. Some campus administrators have blamed their police chiefs for negative press. “They are being hung out to dry,” Cell says.

Training day

The day after the March, the delegation gathered at the Galicia Jewish Museum in Krakow to test drive new training designed by the University of Ottawa Professional Development Institute, Europol and the Miller Policing Center to use the lessons of the Holocaust and other genocides to fight bias, discrimination, and hate crime.

Wall displays depicting the faces of lives cut short or brutally altered lurk in the background like silent warnings. The snippets of joy or carefree normality captured in these photographs demonstrate how quickly hate can take root. It’s an ominous backdrop.

While surrounded by photos and the history of the Jewish Community in Krakow, Paul Cell, Executive Director of the International Association of Campus Law Enforcement Administrators, provides insight into the development of the Senior Police Training Program on Countering Targeted Violence.

Photo/Michael Gips

“How do people become mass murderers? How can you cause one individual to violate fundamental human rights?” asks Dirk Allaerts, an executive director at Europol who is delivering one of the training modules.

Trooper Malik pipes up. “It starts at dehumanization,” he says. Once you perceive someone as less than human, it’s a slippery slope.

Delegation members reading the statistics of those murdered at the Auschwitz-Birkenau. L-R: Marvin Haiman, Visiting Fellow, Rutgers Miller Center on Policing and Community Resilience; former Chief of Staff, DC Metropolitan Police, Colonel Patrick Callahan, Superintendent, New Jersey State Police (NJSP), Tropper I Mudduser Malik, New Jersey State Police, President and Founder of New Jersey Muslim Officers Society.

Photo/Mark Genatempo

It was wise for Col. Callahan to recommend Troopers Malik and Zislin for this mission, the same brand of wisdom that inspired Col. Callahan to hand select six Muslim troopers and six Jewish troopers for a rap session shortly after October 7. “It showed that the New Jersey State Police is ‘on the side of humanity,’” Callahan tells us.

“He brought us together to express concerns, hash out issues and really let us clear the air,” recalls Trooper Zislin. “We six knew and respected each other, most of us had worked together and relied on one another, so we were a good group to start the conversation,” he adds.

There are relatively few Jewish and Muslim troopers, who are particularly well suited to reach out to their respective populations, says Malik. “The connection to our communities is critical. They see us as their representatives and champions, and if we can enable conversations and enhance understanding, we’ve done a great service to our diverse populations.”

Callahan’s initiative has worked. He, Malik and Zisler say that dialog among officers is open and positive, which has enabled their constituent communities to communicate in a respectful and productive way.

Whereas during the Holocaust police helped dehumanize Jews, Roma, the handicapped and other “undesirables,” Goldenberg notes that police have become victims of dehumanization. His training module touched on how the police themselves can teach about dehumanization from a place of empathy. “We feel beaten down and harassed for choosing a career of public service,” he notes. As police try to reclaim their humanity, it informs their ability to convey the dangers of dehumanizing specific populations.

And how to fight dehumanization? “We have to inject humanity into everything we do, both internally and externally,” says Sasha Larkin, assistant sheriff for the Las Vegas Police Department who is responsible for homeland security and investigations. She tells the group about the struggles encountered by the first (and still only) Muslim female police officer hired by her department. “She was treated rudely, even in what was considered a progressive department,” Larkin says. “The problem was that we hadn’t built a culture internally. It has to start there before we can expect it to spread outwardly.”

Bringing it home

Our delegation members wipe away tears, breathe deeply and bow their heads while on the grounds of what is likely the most iconic concentration camp of the Holocaust. But the real impact comes from the concrete takeaways they bring back to their communities.

“It gives a historical perspective of what happens when you let the temporary political whims influence your actions,” says Sheriff Champagne of Louisiana, who also serves as the president of the National Sheriffs Association. “We honor the right to speak, to gather and to protest, and everything else that makes the United States strong. “But that ends at mob rule that leads to threats and violence. We have to respect the rule of law.”

“It’s about talking about issues and finding solutions together,” adds the RCMP’s Gauvin, who says she will bring an increased sense of empathy and understanding back to Ottawa.

At the end of the training day, former Chief of Staff of the Washington, D.C. Metropolitan Police Department Ben Haiman asks his fellow officers to pledge what they will do differently after the mission. Responses involve implementing more nuanced conflict resolution, applying insights to human behavior, sharing the experience with fellow officers and leadership, improving mediation efforts, using active listening skills and conveying the lessons to their own children.

It’s a daunting yet hope-inspiring challenge.

For Troopers Malik and Zislin, the few miles they trudged in and among concentration camps in the heat was the easy part. The road ahead in a divided United States is arduous. But they are walking together.