By Police1 Staff

Phonetic alphabets are meant for radio users to be able to pronounce and understand strings of letters and numbers regardless of signal quality. For example, asking dispatch to run the plate, “VBE-718" might result in a request to re-read the plate. Instead, the patrol officer can save time and make communication more clear by asking for the plate, “Victor Boy Edward 718.”

The police phonetic alphabet, unique to American law enforcement officers, is even more succinct than the military code and useful for communicating information like names and license plates clearly over the radio.

Where did the police alphabet and radio codes come from?

The police alphabet used by officers is similar to the 1956 ICAO phonetic alphabet used by NATO-affiliated military organizations.

The police phonetic alphabet comes from an April 1940 newsletter released by the Association of Public-Safety Communications Officials-International, or APCO.

Even after the NATO alphabet came into use, local and state police departments continued to use the APCO police alphabet to transmit information such as license plate numbers over the radio. In fact, the police alphabet may be even shorter and punchier than its military counterpart.

For example, officers save some extra syllables when they say: Frank instead of Foxtrot Ida instead of India Nora instead of November Queen instead of Quebec

Today, departments as far away as Houston and New York have adopted a form of the APCO alphabet, albeit with a few minor variations between them.

| Get instant access to valuable resources! Download our digital guides tailored for the police industry and elevate your skills and knowledge.

Why use the police alphabet?

Similar letters like D’s and B’s may sound the same over fuzzy radio traffic. Using the police alphabet makes what you’re trying to say more obvious, and minimizes error by clarifying the letters.

Some areas share scanner traffic between agencies, which means that multiple units are listening in at any given time. However, since only one person is able to speak at a time, it’s important that the channel is kept clear in case something urgent happens.

Even though spelling things out using the police alphabet may take slightly longer than using regular letters, it’s still more likely to reduce radio chatter by eliminating the need to repeat messages.

Police departments use a mixture of plain English, 10 codes and the phonetic alphabet in order to keep radio communication as brief as possible.

Is the police phonetic alphabet the same everywhere?

Police codes are meant to be similar enough that officers who transfer positions across the country will be able to understand them. Of course, there are some differences between departments.

LAPD will say “Edward;” NYPD will say “Eddie.” LAPD will say “Lincoln;” NYPD will say “Larry.” LAPD says Paul, NYPD says Peter. There’s also Tom versus Thomas, and Young versus Yellow.

Those minor differences don’t really impede communication between departments. But the other form of police communications, 10-codes, are a different beast altogether.

Phasing out the 10-code system

Though popular codes like “10-4” (“Affirmative”) are recognized everywhere, police radio codes can vary quite a bit between different areas. Depending on where you’re from, a 10-33 police code could either mean spotting a traffic backup, or seeing a downed officer – which obviously aren’t two things you want to confuse.

The problem with having a nonstandard radio code system is that responding to large-scale events like natural disasters or mass shootings requires teamwork between several agencies. During these incidents, police must be able to communicate clearly with dispatch, fire and EMS while eliminating as much confusion and radio chatter as possible.

In the spirit of interagency cooperation, police departments have begun phasing out 10-codes over the past decade. Instead, they’ll opt to use plain English, especially when speaking with other departments who may not share their language.

What is the police phonetic alphabet?

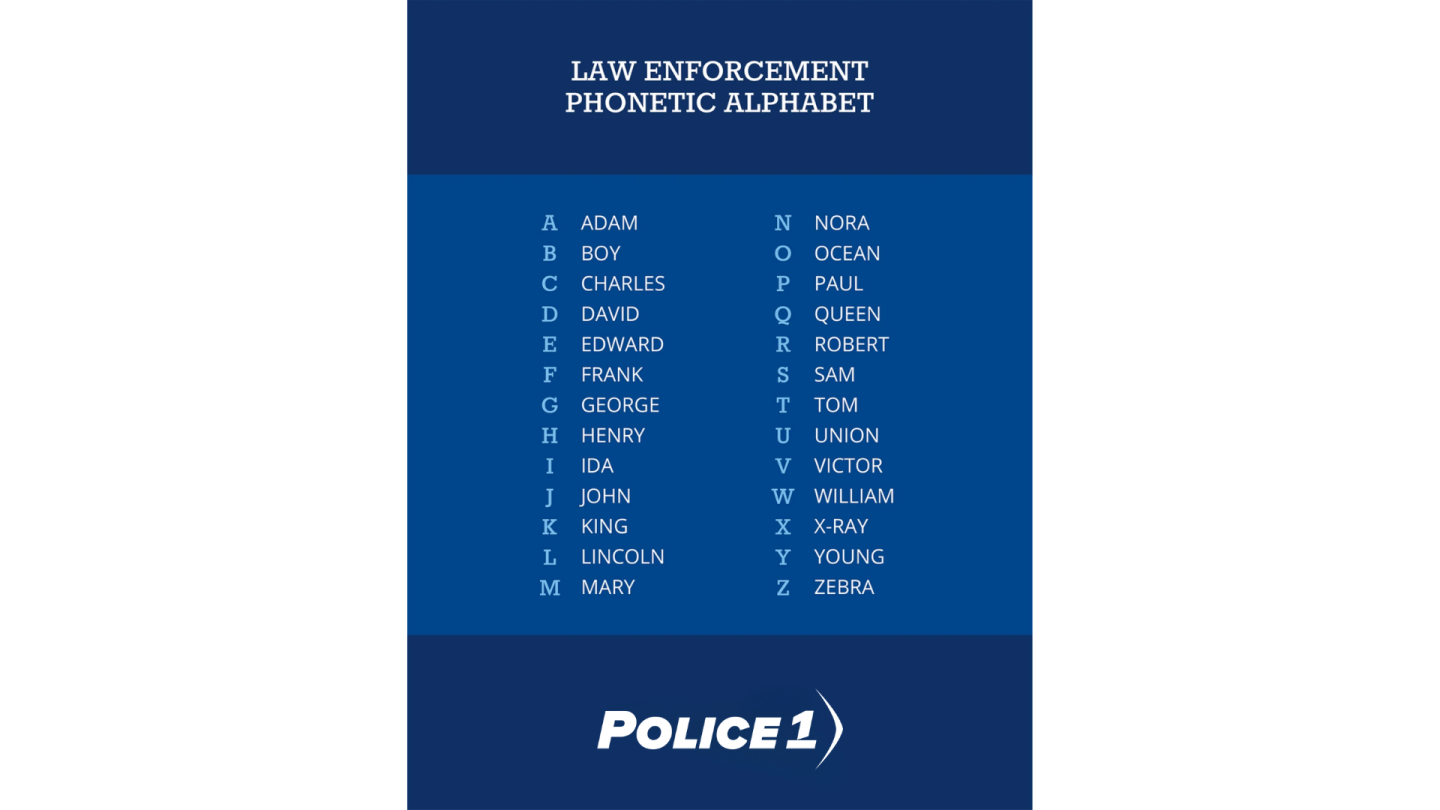

Below is the full LAPD phonetic alphabet for your reference or you can get the phonetic alphabet printed on a coffee mug, facility sign, or as a wall art poster:

This article, originally published September 20, 2016, has been updated with a video and additional resources.