By Megan Wells, Police1 Contributor

The ‘90s were a pivotal decade for law enforcement. Crime rates fell sharply throughout the decade. Across the board, everything from violent crime to property crime declined.

Homicide rates dropped 37.2 percent between 1991 and 1999, which is especially noteworthy considering handgun-related homicides more than doubled between 1985 and 1990.

The drop in crime wasn’t specific to geography ﹘ it was felt nationally.

It’s not like a switch flipped in the ‘90s, and everyone decided to act lawfully. It was a combination of events that lead to the decrease in crime. Police1 has identified these occurrences, and we show how these findings can help continue to improve law enforcement tactics and community relations.

Violent Crime Control and Law Enforcement Act of 1994

This act was (and still is) controversial, but the changes it initiated are impossible to ignore.

According to the U.S. Department of Justice, the bill was “the largest crime bill in the history of the country and [provided] for 100,000 new police officers, $9.7 billion in funding for prisons and $6.1 billion in funding for prevention programs, which were designed with significant input from experienced police officers.”

Certain aspects of the act contributed to the decline in crime, like increased police presence. Other components were not as successful, like the expansion of the death penalty, which, empirically, was carried out too infrequently to have a measurable effect on the crime drop.

Increased jail population

The Violent Crime Control and Law Enforcement Act of 1994 introduced the “three strikes you’re out,” rule and harsher punishments for drug-related crimes.

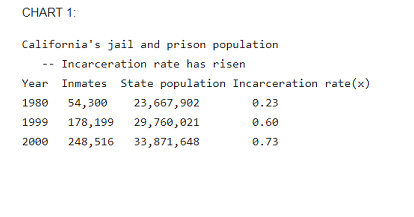

Under the act, California’s prison population grew more than twice as fast as that of the state as a whole in the 1990s. The U.S. census found the number of people incarcerated in federal and state prisons and county jails in California grew by nearly 40 percent between 1990 and 2000 to nearly 249,000 inmates.

(Photo/U.S. Census)

There were implications nationally, too. According to the Bureau of Justice Statistics, the states and the District of Columbia added 52,331 prisoners; the federal system added 6,355. Between 1980 and 1999, the prison population across the country had increased 143 percent to 441,422.

Connecting the increased prison population to the drop in crime seems simple, though it’s difficult to find conclusive data to support the theory.

Researchers, including a National Academy of Sciences panel, have found only a modest relationship between incarceration and lower crime rates. The Brennan Center for Justice at NYU School of Law concluded that incarceration was responsible for approximately five percent of the drop in crime in the 1990s.

However, the three years following the 2014 passage of Prop 47 in California (re-categorized certain nonviolent crimes from felonies to misdemeanors), showed that both violent and property crime rates have increased.

The crack epidemic

A 1986 Gallup poll asked Americans, “Which one of the following do you think is the MOST serious problem for society today: Marijuana, alcohol abuse, heroin, crack, other forms of cocaine or other drugs?” At 42 percent, “crack” and “other forms of cocaine” beat “alcohol abuse” by eight percentage points.

By the 1990s, federal funding for the war on drugs reached $17.1 billion.

The decline in crack use may have had an impact on lowered crime rates (Photo/Wikimedia Commons)

Addressing the crack epidemic was a priority for law enforcement and the federal government.

In 1996, approximately 60 percent of inmates incarcerated in the US were sentenced on drug charges. From 1991 to 1995 the release rate for drug offenders was only 38 percent.

A 1998 Slate article examined the crack and crime spree of the ‘80s and ‘90s. They wrote that “the decline in crack and the beneficent effect of that decline on urban crime rates both seem plausible, but one of the odd things about [articles written at that time] is that only rarely do they have any hard statistics on crack usage.”

This is true. Drug statistics were scarcely tracked and making a definitive conclusion on the relationship between lower rates of drug use and crime rates is difficult.

We can try to compare the crack epidemic and crime trends of the ‘90s to today’s crime rates in relation to the opioid epidemic our country is currently facing.

Crime statistics aren’t ramping up as they did with the crack epidemic.

The murder rate jumped by 5 percent nationally last year, causing concern that the opioid epidemic might be spurring a new wave of crime. The murder rate, however, was largely geographically isolated ﹘ cities like St. Louis and Baltimore were among the most dangerous in the U.S. last year whereas the opioid epidemic is impacting rural areas like McDowell County, West Virginia and Rio Arriba County, New Mexico.

These data points suggest that opioids aren’t necessarily linked to crime, whereas crack may have been. Crime and drug use were prevalent in the same areas when the crack epidemic was in full swing. When crack users started to become incarcerated at a higher rate, crime also went down.

Arrest patterns changed

The Violent Crime Control and Law Enforcement Act of 1994 also provided funding for tens of thousands of new law enforcement officers. With new hires also came new guidelines and training standards.

The diversity of LEOs hired is also noteworthy.

- The percentage of full-time sworn personnel who were members of a racial or ethnic minority increased from 30 to 38 percent.

- Hispanic representation among officers increased from 9 to 14 percent, blacks from 18 to 20 percent, and women from 12 to 16 percent.

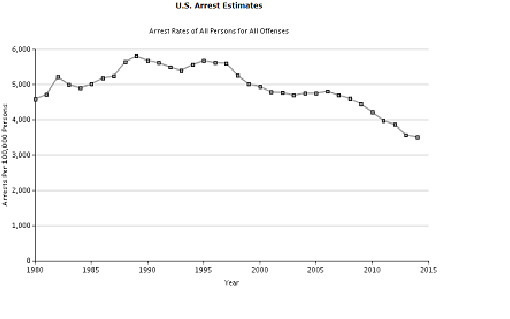

Arrest rates were actually declining in 1994 when the act went into effect but spiked a bit around ‘95. Around ‘97 and ‘98 when legislation was in full swing, and more officers were on the streets, the most noticeable decline of arrests started to occur.

(Photo/BJS.gov)

It could be deduced that an increased police presence, with improved training, slowed crime rates.

However, with every argument, there are two sides. The Brennan Center found a “modest, downward effect on crime in the 1990s, likely 0 to 10 percent” from increased hiring of police officers.

New technology introduced

Dash cams gradually became standard equipment in patrol cars all over the nation.

Lance LoRusso, former LEO and author of the book “When Cops Kill,” explains how the rise of handheld video was a large influence on the negative image of policing.

He explains that the proliferation of handheld video made it easy for civilians to record and compare an officer’s actions to what they had seen on TV or in movies. But, the quality of handheld video was also notoriously poor in the ‘90s, which made it difficult to see the whole story or the LEO’s point of view. This was especially true in the Rodney King case.

Dash cams were introduced as a way to combat this issue, and preserve community relations as best as possible.

Dash cams became common in the ‘90s, and the first federal grants for dash cams were dispersed in 2000. At that time, only around 11 percent of the state police and highway patrol vehicles were equipped with in-car cameras. By 2004, that number jumped to 72 percent.

DNA technology

DNA was first introduced in the ‘80s and was instantly recognized as an invaluable science. In the early ‘90s a five-year project to improve the quality and availability of DNA technology to local and state law enforcement was introduced. By mid-1999 more than 60 people had been released from American prisons following post-conviction analysis of DNA evidence.

In October 1998, the FBI launched the National DNA Index System (NDIS), a nationwide repository of DNA from known criminals and unknown persons at crime scenes. This advancement led to convictions or conclusions for about 200 previously unsolved crimes.

Predictive policing

The Police Foundation established a crime mapping laboratory in the mid-1990s, which allowed for the integration of mapping technology into police work, to focus on the needs of the law enforcement community with regard to crime mapping and analysis.

Each of these technological advancements empowered law enforcement to make strategic and tactical decisions and worked to prevent crime.

Legalization of abortion

Regardless of one’s political and ethical stance on this hot-button issue, there is a body of evidence that suggests the 1973 Supreme Court decision on Roe v Wade also had an impact on crime rates.

The Donohue-Levitt hypothesis is one of the most well-known pieces of work that argues that the legalization of abortion contributed to the decline in crime. And, many economists and criminologists have had a hard time arguing against these claims. By matching abortion regulations and violent crime patterns 18 years after abortion was legalized, Donohue and Levitt argued that the cohort of high crime populations became smaller, leading to a decrease in crime rates.

Opponents of this belief point to the suppression of the crack epidemic and increased arrest rates as stronger contributors to the decline in crime.

To paraphrase a 2005 Freakonomics episode, understanding the impact of legalized abortion on crime is slow and steady and grows a little year by year. Crack came in with a fury and then largely disappeared. So it’s important to take time to understand both abortion and crack.

Still, in the opinion of Freakonomics, there has yet to be a compelling critique of the hypothesis that abortion reduces crime.

What improvements can be made from here to further benefit the future of policing?

The lessons learned from addressing crime and policing techniques showed that a combination of embracing and investing in new technology, and continuing to prevent crime versus reacting it is important to declining crime rates.

Body-worn cameras

Dash cams in cruisers were not a welcome addition to the technology arsenal at first. While the debate about dash cams has cooled over the years, studies continue to show the benefits of LEOs having them.

The newest debate has turned to body-worn cameras. After the first-ever study on body-worn cameras, results appear favorable. Embracing this technology can benefit the future of policing. Similar to the positive impact dash cams have had on policing, body-worn cameras have provided clear and direct evidence of a crime, led to improved citizen and LEO behavior and reduced complaints. There are still kinks to be worked out, but future applications for body-worn cameras, like real-time facial recognition, could be highly beneficial for crime reduction in the future.

Increased awareness of the importance of policing technology

The peaking of the crime into ‘90s made it clear that available policing technology was becoming outdated. As more resources were dedicated to technology, crime rates started to come down, and police found the technology could be used to protect themselves.

LEOs are now dealing with high-tech crimes. As we evolve into the cyberspace, policing technologies need to evolve yet again so LE can continue to fight crime. Advancements like biometrics, improved technical infrastructure and drones are becoming a larger part of the conversation, and more accessible to smaller departments.

Improved technologies for predictive policing

Introduced in the ‘90s, predictive policing proved to be a smart and strategic solution to preventing crime. Predictive policing can now use big data like social listening to recognize probable criminality.

We see crime mapping and improved surveillance for opioid overdoses, like the Overdose Detection Mapping Application Program, which is meant to ensure public health and safety officials have real-time data to respond to an overdose threat or spike.

This is helpful for communities experiencing the crisis, as well as neighboring counties who know they may be hit in the next eight to 10 hours. This heads-up allows EMS personnel, law enforcement, and hospitals to be prepared and ensure they are sufficiently supplied with Narcan or naloxone. Continuing to improve predictive policing has the potential to further prevent crime.