Law enforcement officers are required to do one thing extremely well on every call, traffic stop and public contact: make decisions. There isn’t a shift that goes by that doesn’t require officers to make good decisions. With this in mind, we are missing a great opportunity if we do not work decision-making and problem-solving into our live-fire range training. As a result, aside from skill-building drills that focus on developing or improving the performance of one or two skills, most of our firearms training courses of fire should include decision-making and problem-solving as one of the performance objectives.

Traditionally, firearms training has been more about the physical application of technique. This has resulted in improved performance by the end of training sessions. Multiple repetitions of techniques and skills on the range lead to good performance short term but poor retention and recall of skills long term. Instead of focusing on short-term performance gains, firearm instructors should focus on long-term retention of skills.

Power of the subconscious

A way to improve long-term skill retention and develop high-performance shooters is to make the process of shooting well quickly and accurately a subconscious skill instead of something students need to consciously focus on. If students need to consciously think about their stance, their grip, their sight picture, their trigger press and every other little thing needed to shoot well, they will never develop the skill necessary to make that shot under stress and time duress.

Instead, once a student understands the basics of stance, grip, sight picture and trigger press, instructors should be pushing the limits of their performance by adding time duress and decision-making to the process. This helps move the process of shooting to the subconscious mind freeing up the conscious mind for the real important role of decision-making and problem-solving. When the process of applying marksmanship becomes a subconscious process, students will perform better long-term and while under stress.

The difference in performance between the conscious mind and the subconscious mind can be enormous. A good example is learning to drive. When we learn to drive, everything we do takes conscious effort. The amount of accelerator, brake and steering input all require us to think about what we’re doing. If you learned to drive a vehicle with a manual transmission, it further complicated the process by adding a clutch. However, after some training and time behind the wheel, most of the accelerator, brake and steering inputs have become automatic like you’re on autopilot. This is the subconscious mind taking over the tasks associated with driving. Add in requiring the use of turn signals, and it’s easy to see that most drivers on the road still haven’t developed subconscious competency for driving!

OODA

United States Air Force Colonel John Boyd developed the OODA Loop as a decision-making cycle for combat operations. Observe-Orient-Decide-Act provides a framework for the application of decision-making and problem-solving in firearm training drills. When we examine each step of the OODA Loop, three out of four categories are cognitive-based. Act is the only step in the process that is physical.

Unfortunately, traditional law enforcement firearms training has put the most emphasis on the “Act” part of the OODA Loop with very little focus on the rest of the decision-making cycle. The result has been that the basic skills required to shoot well (the fundamentals) have remained in the conscious part of our minds because there is nothing else for the conscious mind to focus on while shooting.

Instead, once the foundation has been laid and shooters can consciously apply the fundamentals of marksmanship, it’s time to add a cognitive component to training. The cognitive component of drills should force the shooter to observe the problem, orient themselves to the challenge, come up with a decision as to how to solve it, then act to apply the solution. This can be done in any number of ways limited only by the imagination and creativity of the instructor.

Problem-solving

A good way to include a cognitive aspect to live-fire training drills is to design a drill where the shooter must solve a problem and place accurate fire on the solution. An example of this would be a drill designed by students in one of our Building Better Shooters Advanced Firearm Instructor Courses. The drill, Math is Hard, uses this target, but any type of similar target would work just as well.

The shooter begins with 3 rounds loaded in their pistol. The instructor will call out a simple math equation (ex. 5+3). The student will draw and fire 3 rounds to the solution (8).

The shooter then moves to a cover position while reloading. From cover, the shooter fires 3 rounds to each number called out by the instructor (ex: 5+3 = 3 rounds to number 5 & 3 rounds to number 3). Hits inside the shape count as +1 point. Each run has a total of 9 pts possible.

This drill forces the shooter to think about the numbers called by the instructor, remember the numbers called, solve the math equation while shooting the numbers in the equation, shoot the solution to the math equation, move to cover while reloading, and remember the last number called. There’s a lot going on to occupy the conscious mind with this simple drill.

Run this drill twice without time duress to help shooters understand the drill. Then, run the drill three times using a shot timer with a 10-second par time. With 9 pts possible per run, five runs would be 40 total points possible. It’s plenty of time but operating under time duress compresses the amount of time the shooter can consciously think about the solutions forcing them to shoot using their subconscious mind. Once 10 seconds becomes easy, cut the par time down to 8 seconds.

Creative solutions

Another way to add a cognitive aspect to firearms training is to set up a course of fire that can be run multiple ways and give the shooter the freedom to decide their most efficient and accurate way possible. Keep in mind the goal here is to force the shooter to think about the best and fastest way for them to solve the problem, so there are going to be many different solutions depending on their skill level and individual strengths and weaknesses.

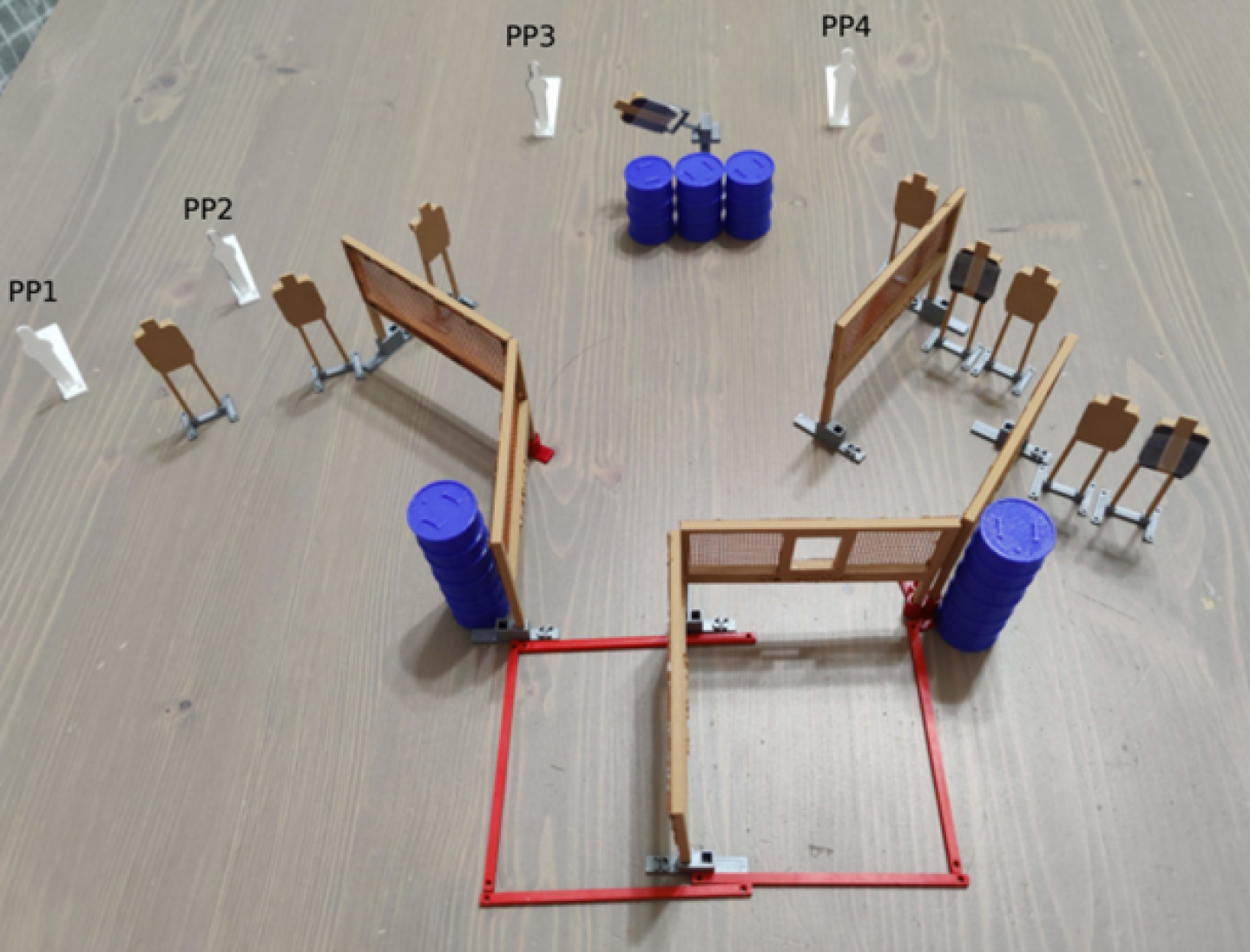

This course of fire is an example of how to give shooters the freedom to decide how to solve the problem. This was a stage designed by Gil Yolo for the 2023 Texas State Open USPSA Championship.

Start by standing anywhere inside the shooting area (marked by the red sticks). Using a shot timer, engage all targets as they become available from within the shooting area. PP4 activates the swinging target.

This course of fire is scored using the best 2 hits per paper target, the steel must fall to score. Time stops on the last shot fired. Even though this was a USPSA stage, you could use any target with a reasonable center mass scoring zone and apply penalty time for shots outside the center mass area. You could add no-shoot targets, remove targets if you have a limited number available, or make whatever modifications you want to meet your training objectives.

Decision-making

Here’s another challenging drill that Chrystal Fletcher came up with to challenge a wide range of marksmanship skills. This drill, named Dammit, has a few simple rules:

- Shooter must engage each plate with a total of two rounds.

- No plate may be engaged with two consecutive rounds.

- Each target transition must be made in the opposite direction as the transition before.

We like to run this as a blind drill. After giving shooters time to study the rules and this diagram, we take them to the range where we have added several targets and staggered them at different distances to make it look more complicated. We will give them 20-30 seconds to update their plan, then we start them using the shot timer. If they complete the drill successfully by following the rules, then they get their time. This drill is a great example of decision-making and problem-solving under time duress.

Utilizing these concepts to move the shooting process from the conscious mind to the subconscious mind can provide better long-term retention and recall of skill under stress and time duress. We can train shooters to make faster decisions, better decisions, and apply marksmanship quicker and more accurately when we free the conscious mind to focus on critical threat assessment and decision-making tasks. The time to develop shooting skills at the subconscious level is in training so that officers can perform better on the street.