By Gary Klivans

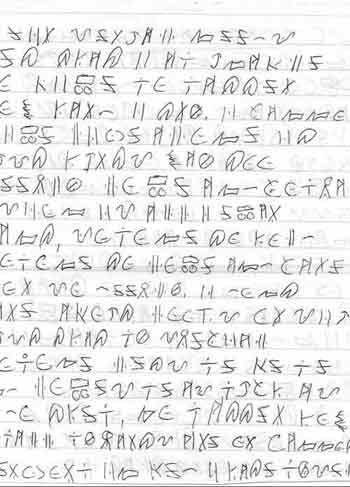

“Help! What does this message say?” This is the request that came with six pages of a suspected gang code that had been confiscated by the Tennessee Department of Correction and was forwarded to me through law enforcement channels. Two of the six pages are shown here. (See Illustration 1 & 2)

Illustration 1 |

|

Illustration 2 |

|

As I examined the individual pages, I didn’t see any familiar known gang symbols. This has happened before, when a gang member doesn’t use obvious gang identifiers to try to hide his affiliation.

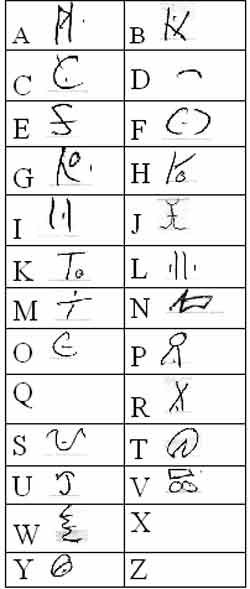

I was able to determine some specific patterns, which enabled me to decipher this questioned suspected gang code and allowed me to provide the good folks in Tennessee with the following table which they could use to read these six pages and any future documents they might confiscate from this suspected gang member. (See Illustration 3)

Illustration 3 |

|

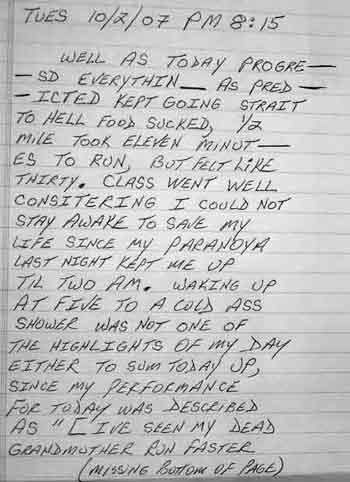

The six pages turned out to be an inmate diary. The writer is apparently incarcerated in a “Boot Camp” setting and is complaining about various aspects of his current life style. (See Illustration 4)

Illustration 4 |

|

After deciphering the document I shared this information through law enforcement channels. Every time I forward gang code information to agencies around the country, I am always contacted by a variety of agencies from different jurisdictions at the Federal, State and Local level.

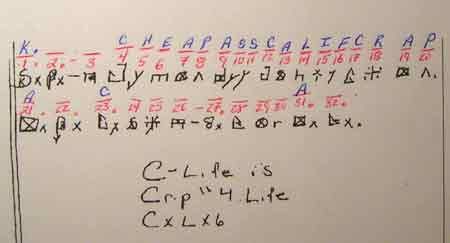

One of the people who contacted me after I sent this material out was a Lieutenant from an East Coast State Police agency. He asked me if he could send me a questioned document that he said used a Crips gang code. He explained that he had a three page letter and that at the end of the letter was a coded message that was less than two lines long. I told him that this was an extremely small sample and would be very difficult to decipher and with that understanding he sent me the following sample. (See Illustration 5)

Illustration 5 |

|

I will never criticize this Lieutenant for sending me a code challenge that is “too easy”! After examining this small sample, I began to think that the last four symbols in line one might be “CRIP.”

But after trying to use those symbols as those letters I found that what I expected to be the letters “I” and “P” at the end of line one was actually “A” and “P”. I made a template by giving each symbol a number and plugging in the letters that I now had.

I continued working on the sample a little more, and I was able to return the following information to the State Police Lieutenant. (See Illustration 6)

Illustration 6 |

|

The portion of this sample that I numbered (4 to 20) said “cheap ass calif crap” (cheap ass California crap). Symbol (1) is the letter “K” which is the first initial of the recipient’s first name. After conferring with the Lieutenant I determined that the letter “D” began the recipient’s last name, so symbol (2) would be the letter “D.”

We also believe that symbol (22) is the letter “B.” With such a small sample to work with it is impossible to verify what is sometimes speculation. The State Police Lieutenant was thrilled that I was able to provide him with this partial translation. I, on the other hand, was not as happy. I prefer to be able to decipher every symbol with certainty.

As the Lieutenant thanked me for my effort, I began to understand why he was so happy when he said “At least I know that the message isn’t about killing one of my Troopers.” At that point I realized what he was afraid the coded message might have said and I also realized that the Tennessee coded document could have been six pages of specific instructions about a homicide, escape, threat to a law enforcement officer or information about a terrorist attack, not just an inmate diary.

Not knowing what a code says can give us nightmares. We need to know what these gang codes say, but sometimes we need to know “what they don’t say” even more.