Contemporary police trainers recognize the value of replicating circumstances likely to be faced on the street, and providing students with opportunities to put their skills to the test-and correspondingly increase the probability of a positive outcome during an officer/suspect encounter. Whether this involves soft empty hand control while teaching basic handcuffing, or dynamic, full-contact force-on-force training, “realistic and practical” have become watchwords in police training today — and with good reason. Inserting tools and techniques into an active and competitive environment peels back the onion on practical student performance capabilities — specifically as it relates to their knowledge, skill, strength, decision making, and physical conditioning. This alone is beneficial, as it allows both student and instructor to critically examine capabilities in circumstances that mirror in a reasonably controlled environment, the challenges they may face in the real world.

In addition, subjecting the student to a dynamic encounter where the outcome is uncertain — and where in fact they might not prevail — brings a sense of urgency to training that you just can’t get any other way. Regretfully, this environment does not come without risk. Police1 Columnist Captain Greg Meyer — recently retired commander in charge of the Los Angeles Police Academy — addressed this issue when he wrote:

“Law enforcement training is physically rigorous and demanding. It is an essential objective of law enforcement training to prepare officers as realistically as is reasonably possible for the threats and circumstances they will face on the street. It is essential to train law enforcement officers how and when to use various items of equipment, including nonlethal weapons, and to understand their utilities and effects. Such training is essential so that the officers will know as much as can be reasonably known about the weapons, their operation, their possible effects, and what are the risks and consequences if the officer is disarmed and/or overpowered by a suspect. Because of these legitimate needs of law enforcement, and realistic training must be physically challenging, it is inevitable that injuries will occasionally occur.

Police1 Editor Doug Wylie added to the dialogue when he emailed this author a note containing the thoughts of a friend and police trainer he knows, “I will not be afraid to lose a little blood in training, lest I lose all of it in the real world.” Conceptually, I believe most trainers and officers are there. We all know you can’t make an omelet without cracking a few eggs, right? If only the issue were that simple.

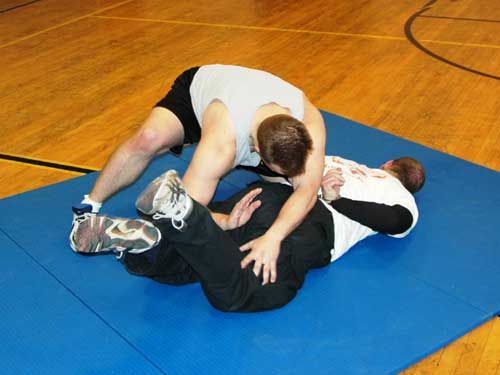

Two officers participate in a grappling training exercise

Commitment to the simplistic and practical “train as you fight” mentality is easy to express in words but becomes much more problematic when the injuries follow. Based on past experience, they will (at least to some degree). A search of the published literature reveals numerous reports of injuries occurring in the training environment in recent years, ranging from minor sprains and strains to permanent injury and death. Some of the more common themes involve:

• An officer claims the electricity received during electronic control device training fractured his back and caused other severe injuries — the officer further alleges that the manufacturer did not fully disclose the risks associated with being exposed to the device

• An officer claimed that he received a corneal abrasion after being shot with OC spray during training

• An officer alleged that he was burned when an electronic control device was alligator clipped to his body, and the burn later became infected

• An officer claimed that he suffered an eye injury during force on force training due to the chief making officers wear riot helmets during the exercise instead of specially designed face masks

• An officer required major reconstructive knee surgery following the application of a “common peroneal” strike that missed the mark during training

• An officer received a disabling injury after being accidentally struck on a non-target area during a baton training exercise

• An officer received a permanent and disabling neck injury during training on the application and escape from a carotid restraint

• A police recruit died from a brain bleed after being punched into unconsciousness by a trainer during a ground fighting exercise

• An officer was shot and killed during active shooter training, when a real firearm was inserted into the exercise where only simulated firearms were permitted

• An officer receives an internal injury after being struck in the abdomen by a “bean bag” round during a training demonstration

• Three dozen officers reportedly suffered concussions over the past 10 years in a boxing program that also included a trainee’s death, and another being paralyzed

• An officer falls to his death during a rappelling exercise

This article is not about the training programs referenced above, or the best practices for avoiding injury to those participating in them. It is about officer exposure to physical force and or physical risk in training and the need to critically examine the logic, rationale, and motivation behind such exposure — especially in cases where it is not required to master the skill set involved. As an example, recruits being taught prisoner control and handcuffing need to physically lay hands on a human “suspect,” and place them in restraints while facing varying amounts of resistance. This training will expose the recruits to the risk of being injured, but prisoner control and handcuffing are fundamental tasks in law enforcement and you just can’t learn it any other way. As such, when the risk/benefit is analyzed, benefit clearly wins out. It is my opinion and belief that this concept should be extended to all areas of training involving physical risk, and the risks then logically compared to the benefits of exposure-not just for the trainee, but for the training program/agency itself.

In consideration of this, does an officer really need to be exposed to an electronic control device (ECD) in order to safely and effectively use it? I think not. The manufacturer doesn’t require exposure independent of awarding their most senior instructor/trainer rating — and beyond question that is within their authority to do so. So why then do some agencies under threat of discipline compel officers to be exposed? The most common answers revolve around a belief that ECD exposure will enhance product confidence, and better prepare officers for situations in which an ECD might be used against them on the street.

In response to this I would first acknowledge the popularity of YouTube, and then offer that I find it hard to believe anyone in the galaxy or beyond lacks confidence in the ECD. In addition and from a practical standpoint, there is nothing anyone can do to physiologically “prepare” for an encounter with an ECD-wielding suspect — absent getting away from it. You don’t need to “ride the lightning” to figure that one out.

So is there any benefit to being exposed? I think yes. Exposing students graphically demonstrates the difference in performance potential between a contact/close probe deployment, and probe deployment with adequate spread. Secondarily, exposure is a practical way of providing training in probe removal and post treatment. Third, exposure provides students with the opportunity to experience handcuffing under power in a controlled environment, and learn first hand that it can be done without subjecting the contact officer to the electrical charge involved. There is a training value in each of the scenarios outlined above, but insufficient value in my opinion to compel officers to do it. Based on personal experience, I believe an instructor that can effectively communicate the logic behind exposure will end up having almost 100 percent of the students volunteer. In the absence of that, I believe compelling officers to be exposed simply doesn’t make sense.

Statistically, the risk of being injured in a student exposure scenario is around one in 40,000 (data provided by the leading manufacturer). Compare that with any other type of physical activity, and it becomes readily apparent that exposure to the ECD is “safe” by any reasonable definition from an injury perspective.

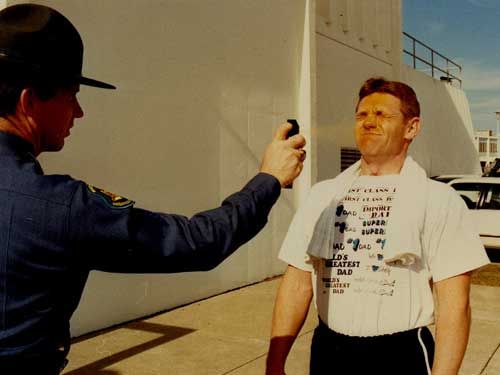

Master Instructor Chris Johns volunteers to be exposed during a TASER training

As such, the risk/benefit consideration does not involve a significant risk of physical injury as compared to the benefit of training, but a risk to the ECD program itself. People who are forced to do things they don’t want to do-especially things that cause physical discomfort-have a way of pushing back. This can take on a life of its own as grievance processes are pursued, back door complaints made to city counsel members, and the issue being aired on local talk radio and in the press. The end result is the agency ECD program is needlessly painted in a negative public light. In my opinion, it is simply too valuable a program to risk such preventable exposure-no pun intended.

Does the same logic apply to exposure to Oleoresin Capsicum (OC-pepper) spray? In my opinion it does not. If you work for an agency that uses OC spray, the question is not IF you will be exposed operationally but WHEN-and how bad. The first time this happens should not be when you are fighting over your gun in a back alley, but in a controlled environment where you can assess the effects, learn how your body will react to the agent involved, and work through the panic that naturally comes absent past experience. Exposure in this case is not about the safe and effective deployment of the product, which can be accomplished in relatively short order using inert canisters and a training partner. This is about life and death, as your untrained “first time” response to the agent negatively impacts your ability to fight back.

I am not suggesting that exposure to OC is therapeutic, or that once exposed in training you are immune to its effects and able to react to an assault in top form. I am suggesting that you WILL get sprayed with OC during your police career, and your past exposure experience — with knowledge gained during and your reaction to it — will better prepare you to respond to the task at hand. This could potentially prove life saving and as such; I believe the benefit of compelling exposure is worth the push back baggage that might come with it.

Missouri State Troopers participating in an OC exposure training program

In conclusion, police trainers today need to recognize that there are varying degrees of risk in the programs we offer, and that the first step in mitigating such risk is to ensure that our programs have been assessed pre-event, from a risk/benefit analysis perspective. This is not to suggest that we will no longer physically mix it up in the academy and in service training-on the contrary-using the risk/benefit assessment process as outlined above will likely result in agencies concluding that some of the most aggressive training available may in fact be the most productive.

Likewise, it is incumbent on those operating in the dynamic police training world to ensure that students are only exposed to risk in a well thought out and logical fashion, and then only when the benefit for such exposure outweighs the risk. This should be done not because we are getting soft when it comes to training, or are hyper sensitive to concerns about complaints, civil litigation, etc. It is because we care about our students, and the first step in protecting them from the risks they are likely to face is to prevent them from being subjected to internal risks that we control. This includes exposure to tools, tactics, techniques, and instructor cadre that can resemble trial by ordeal, as compared to effective and practical training. This can be potentially problematic-from both a physical and program injury perspective.

We need to pick our programs and related battles wisely, and ensure that we do what we do for the right reason-that being the overall well being of our students and the communities they serve.