An interesting and somewhat unique part of Northern Ireland’s past troubles involved the arrival of the summer marching season. The vast majority of the world enjoys a parade, but in “The North” they were a part of the cultural tradition of political expression, and a regular source of conflict, rioting, and related violence.

To a lesser degree, the United States has its own marching season. Ours occurs every four years, and revolves around the presidential election. Various groups with diverse opinions assemble during this time, and many agencies ramp up their public order protocols in anticipation of problems that might potentially evolve. The year 2008 brings another “American marching season,” and with it discussions on tools and tactics to manage public disorder.

The purpose of this article is to offer an overview of chemical munitions, and the role they can potential play in dealing with violent and destructive crowds.

Chemical agent deployment philosophy

Chemical munitions are less lethal tools used that can be used to engage dangerous and/or destructive crowds. Contrary to popular belief, they are not “first strike” public order options, but appropriate for use only after properly trained officers have tried less intrusive methods-and found them ineffective. This is especially true when considering that in most public disorder situations, a majority of those present are not involved in illegal activity.

When facing public disorder scenarios, incident commanders should first ensure that adequate dispersal orders have been given via loudspeaker, and consider displaying signs or placards proclaiming the same orders since effective oral communications in crowd situations are often impossible. Chemical munitions have no conscience, and are unable to differentiate between rioters, store owners, or elderly downtown residents. As such, chemical agents should only be considered in situations where those in the crowd are taking action that is in direct violation of the law (destructive or dangerous), they refuse orders to disperse, and the need to use the gas outweighs the concerns inherent in its use-including concerns about contaminating uninvolved people and the surrounding areas.

Upon determining that the deployment of chemical agents would be reasonable and necessary, the incident commander must consider a number of factors including but not limited to: crowd type, specific behavior, countermeasures present (gas masks, etc.), and area of operation (open field, business district, residential area, open streets/highways, etc.). He/she must then make decisions related to agent type, dissemination method, quantity to be deployed, and a combination of tools and tactics that:

• are most likely to accomplish the mission objective

• are safest and most expedient for the grenadiers

• have the least potential for causing collateral contamination

Deployment considerations:

1. Agent type, dissemination method, and quantity involved

When discussing public order gas plans, the vast majority of officers immediately assume that the default process involves CS continuous burn grenades, and “lots of them.” The practical reality is the totality of circumstances will dictate such things, and in many cases “the default” — copious amounts of CS delivered via continuous burn grenades — will bring more baggage than benefit. As noted above, there are many factors that impact exactly where a multi-thousand gram cloud of CS will go, and once released it can never be brought back.

With that in mind, contemporary public order managers — if they deploy hot gas at all — would deploy the agent in a more focused and discriminate manner, to increase the probability of exposing those who need it while reducing the likelihood of affecting those who don’t.

As an example, officers facing a riotous crowd on an apartment complex parking lot near a major thorough fare would likely resolve the problem without resorting to hot gas grenades. The incident commander would first consider the factors unique to this event:

• Apartment complex parking lot: This means significant numbers of uninvolved persons-including children-would be occupying the structures in the immediate vicinity, and subject to secondary exposure should copious amounts of hot gas be used.

• Operational area near a major traffic way: Copious amounts of hot gas could negatively impact driver safety, even after the crowd has been dispersed and the roadway opened.

He/she would then make every legitimate effort to mitigate the problems at hand without resorting to force or chemical agents. If those efforts failed and it was determined that “tactics” were necessary, he/she would factors (outlined below) such as wind and the available escape routes, then likely deploy as the first option chemical agents via aerosol dispensers. This application would most likely be “over spray,” in an effort to create discomfort in the nose and throat while allowing those involved to see and easily leave the area. If this failed they might then use the liquid aerosol in a direct application role, or consider using devices less intrusive than hot gas such as 37mm muzzle blast rounds.

As noted, progressions of this type generally involve MK9 and or MK46 OC dispensers directed in front of and above the crowd first, to create discomfort without closing their eyes. Those who remain and continue to violate the law would be subject to either direct application of the OC, or exposure to minimal doses of gas via muzzle blast 37mm rounds at 50 grams of CS each. Should this effort fail, additional consideration might be given to more intrusive measures such as skirmish lines advancing on the crowds and forcing them from the area. Based on the circumstances outlined above, it is highly unlikely continuous burn grenades would be a viable option.

2. Wind

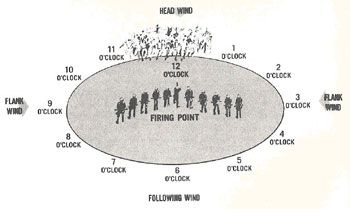

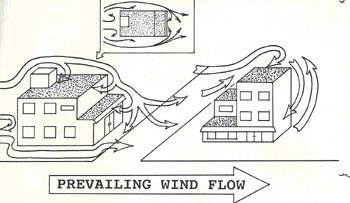

Graphic 1 |

One of the most important issues when considering a public disorder “gas plan” is assessing the wind. In order to avoid confusion, the wind clock shown above is often used to provide general (head, following, or flank winds) and specific (“1, 2, or 3 o’'clock”) descriptions of wind direction, with the heading being determined by the point officers would engage rioters if they were deployed in a skirmish line. Wind direction is critical in that it is the primary vehicle by which the chemical agent is transported from the deployment point to the rioters.

Indirect or area chemical agents should never be deployed unless adequate escape routes are available and when possible, the wind should be used to carry the agent and “push” the crowd (pain aversion principle) towards the escape routes-and out of the area of operation.

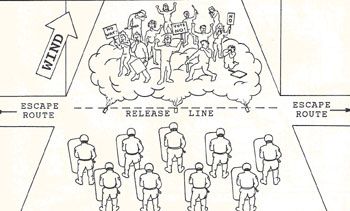

Graphic 1 shows a gas plan that ignores this principle, and would likely yield less than positive results. The wind by definition is following at 6 o’clock, and the escape routes are at the release line. In order to “escape” the effects of the gas, the rioters would have to move head on into the munitions cloud. Based on the pain aversion principle, this would be problematic at best.

Graphic 1 |

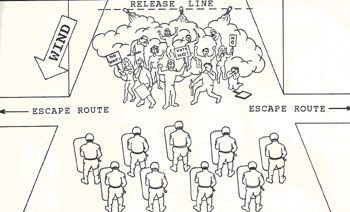

A more logical and effective approach would involve the gas plan shown in graphic 2. The wind is heading at 12 o’clock, so the officers would deploy gas to the rear of the crowd. This would push the rioters forward, and allow them access to the escape routes-and freedom from the discomfort. It is important to note that this also initially moves the crowd towards the officers-which could create problems of its own-and is a reminder of the mandate for gas masks for all police personnel on the scene of any scenario involving chemical agents. The question might then be asked, what if officers had the following six o’clock wind outlined above and did not have viable escape routes at the rear (direction wind/gas would push offenders)? The answer is that you might have a situation in which gas is not a viable option-which regretfully, is often the case.

Graphic 2 |

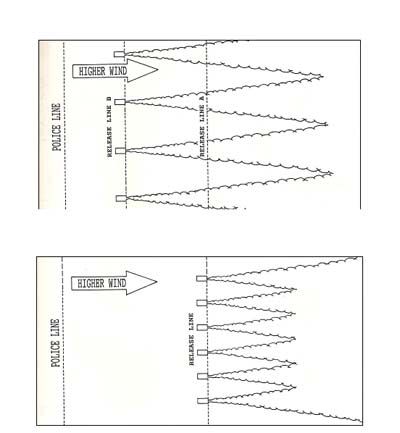

COVERAGE — In the perfect chemical agent world, gas from continuous burn grenades that are spread 5 yards apart with a following 6 o’clock wind of 5-10 mph, will travel approximately 25 yards before forming a continuous cloud. Stronger winds require more travel time/distance to form a continuous cloud, or more grenades spaced closer together (as demonstrated in graphic “3”). The continuous cloud is needed to ensure that everyone in the crowd is fully and equally exposed. It is important to note that due to a wide variety of factors beyond the control of the grenadier, planning for this cannot be done to a mathematical degree of certainty. Understanding the basic principles and then training in a variety of wind conditions generally yields the most positive operational results.

Graphic 3 |

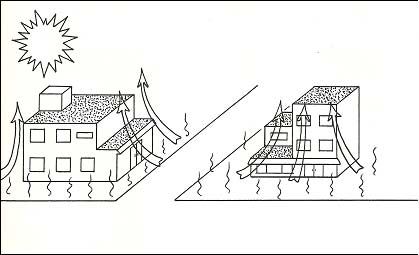

3. Turbulence

Wind direction and intensity are important issues to consider when creating a public order gas plan, but an equally important consideration is turbulence, and the role it can play in manipulating the wind and altering its agent carrying capabilities. Mechanical turbulence is created by the wind moving in and around physical obstructions, similar to the way a wall of water would move if released in the same environment. Assuming that the officers are standing at the bottom of graphic “4,” the flanking 6 o’'clock wind takes on a dramatically different and less predictable path when subjected to the downtown buildings. Add to that the effects of temperature-specifically heat and gas rise (as shown in graphic E), and it becomes clear that there are a variety of factors that impact an officer’'s ability (or inability) to predict the contamination/exposure path of large amounts of agent following release.

Graphic 4 (Mechanical turbulence) |

Graphic 5 (Thermal turbulence) |

In summary, our goal in public order chemical agent situations is to expose the violators to enough gas that we can modify their behavior, and hopefully cause them to stop their illegal activity and leave the crisis site. We must balance this desire with the understanding that chemical agents can be problematic, when we fail to balance our response with the problem presented (overly aggressive/adventurous police actions, too much gas, etc.), or expose persons and or property that are not a part of the violent disturbance.

In order to manage this issue, incident commanders need a thorough understanding of the relevant issues, and must formulate a gas plan-if gas is to be used-that thoughtfully considers the totality of circumstances present and potential outcomes involved. It is important to note that statistically gas-especially copious amounts of or “hot” gas-are rarely needed, called for, or used in American police operational situations. Likewise, when gas is needed, it can be an extremely effective and safe way of moving trouble makers from their area of operation.