Ten years ago today, police officers from NYPD and PAPD had been working around the clock for a full month in the ongoing recovery effort at the World Trade Center. By all accounts, the ground was still hot, smoke was still rising from smoldering areas of the scene, and shards of human remains were still being recovered on an almost daily basis. This is part of the 9/11 story that is rarely remembered — at least not well-enough remembered, in my opinion — so, when I was in New York City for the 10-year anniversary of 9/11 last month, I sat down with Police1 Member Corey Cuneo.

Cuneo, a veteran member of NYPD ESU who on that day was assigned to Brooklyn South Narcotics, had just completed a shift serving warrants and making arrests until 0500 that morning. He was asleep in bed when he got a phone call from his kid brother, who was a construction worker in lower Manhattan, “Get out of bed, you’re going to have to go into work. A plane just hit the Trade Center.”

“Yeah, right,” Cuneo replied before hanging up and going back to sleep.

Anytime, Baby...

The phone rang again 20 minutes later — the kid brother again. Cuneo turned on the TV, saw what was happening, and started making calls of his own — to the same guys he’d just been busting drug criminals with four hours earlier.

“We going in?” someone asked him.

Cuneo answered, “We’re going in.”

“They didn’t recall us yet,” came the reply.

“We’re not waiting for a recall,” Cuneo countered.

This conversation — in one form or another — undoubtedly happened between countless officers of the New York City Police Department and officers of the Port Authority Police Department, but might have held a fraction more electricity for anyone who had ever been associated with NYPD’s Emergency Service Unit.

Years before 9/11, ESU had adopted the icon of a tomcat as its “mascot” of sorts, in part because of the paint job on a squadron of F-14 Tomcats. Beneath the image of a cat on the vertical stabilizers of those fighter jets read the motto, “Anytime, baby,” which NYPD ESU adopted as its own.

“One of the first things that you get in NYPD is a mobilization card,” Cuneo told me as I sat in his 13th floor office just a handful of blocks from the Trade Center Memorial. “The mobilization card tells you where to go when you have some sort of super-emergency. Everybody always laughed because we were never going to need them. I’d ask, ‘What does your mobilization card say,’ and they’d say, ‘Well, ah, I haven’t updated it in ten years.’ And I’d say, ‘Yeah, well nobody has, because we never figured we’d use it. Let’s go, we’re going in. Meet me the Narcotics building and I’ll meet everybody there’,” Cuneo said.

And so, they all did.

A Herd of Cats

As Cuneo drove across the Verrazano Narrows Bridge into Manhattan, he watched the first tower fall and tightly gripped the steering wheel of his car. He got to his destination and strode into the building with his AR-15 slung across is body and a bag full of extra magazines in his hand.

One detective commented to another, “I don’t know where he’s going, but I’m going with him.”

But Cuneo knew he wasn’t going anywhere for at least a little while. In the initial hours after the attack, there were literally hundreds of cops taking off in ones and twos to various locations, and Cuneo wanted to have a more coordinated approach. He told his Sergeants, “Wait until you have six uniforms, then you can go down there. Don’t just go there, find out where the City wants us, and go there.”

It went like that for a while, until Cuneo was confident the effort was organized. Then he himself went down. “I grabbed a bunch of guys, and since nothing was going into Manhattan by bridge, we all piled onto this water taxi.”

Cuneo and his men worked the perimeter that day, and the following day he was assigned to “some random corner” so he called a friend in ESU and asked to be reassigned to the unit temporarily.

Almost immediately, he was.

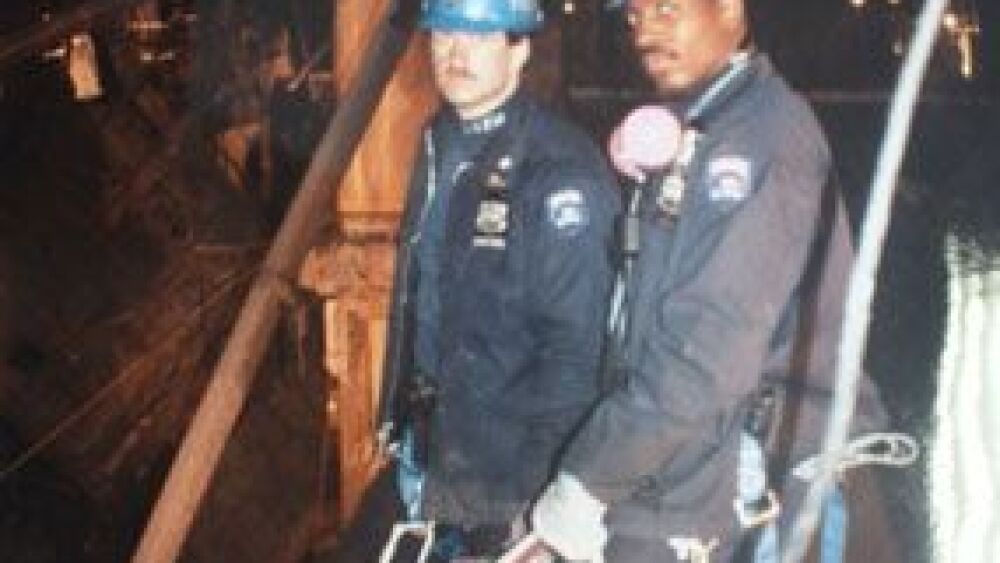

Remembering the Recovery

The recovery effort was one of the most complicated, labor-intensive, and difficult ever conducted anywhere. NYPD’s Emergency Service Unit — which at the time had 430+ highly-trained officers in its ranks — supplied as many as 120 men per shift, with between three and four 30-man teams working in constant rotation alongside firefighters of FDNY. Every two hours or so, everything would come to a complete and total halt — every piece of equipment shut down — so microphones could be dropped into drilled holes in an almost fruitless attempt to hear a survivor tapping out a signal.

At one point in the process, Cuneo talked with an engineer from the United States Army Corps of Engineers. “I don’t get it,” Cuneo said to him. “We’re not finding anybody. Nobody.”

“Look, Lieutenant, you’ve got a 110-story building stuffed inside a seven-story box. Nobody else is coming out of there.”

The weeks passed, and that engineer was proved to be right. Searchers would have to smell the shoes they found to determine whether or not there was any human remains contained therein to be checked against the vast DNA database of the missing.

“We’re smelling shoes,” Cuneo said, incredulously, as we sat in his office on the Monday after the 10-year anniversary. “We’re not looking for bodies. We’re smelling shoes.”

Cuneo described the scene as “nothing but grey powder and grey paste.”

“You didn’t find things that made sense — you’d hardly ever find anything at all,” he said. “There were eight million telephones in those buildings. Once in a Blue Moon you’d come across a receiver. There were thousands upon thousands of doorknobs in those buildings, but only every once in a while you’d find one. The whole building was made of glass, and you’d hardly ever find any glass. One night I came upon something shiny and checked it out. It was the metal fixture for a bathroom sink. No sink, nothing else at all — just the faucet and knobs. It was like that for months. That’s when the monotony began.”

The Coffee Lieutenant

Cuneo told me that once the routine began to set in at the recovery site, other routines began to develop elsewhere as well. One such routine was the fact that just to get to WTC, all those first responders had to pass through as many as four checkpoints a night. Those check points were typically manned by officers from agencies from all over the Untied States. There were coppers from all over — places like Virginia, North Carolina, Texas, Alabama, New Jersey, Massachusetts, you name it — standing around in the cold winter night, checking IDs of officers like Cuneo.

One of Cuneo’s own personal routines involved getting coffee from Dunkin’ Donuts en route to the site. Having passed these LEOs from all over the country every night, Cuneo decided to not just get his own coffee, but instead, fill one of those four-cup carriers. At every successive check point, he’d ask if anyone wanted a cup, and pass them out as he went along.

“One night, I don’t remember exactly when, I get down to the Brooklyn Battery Tunnel. There’s a few New York State Troopers standing there, so I roll down my window and say, ‘Hey, anybody want a coffee?’ A female trooper walks over and says ‘Yeah, sure I’ll take one, thanks.’ ...She looks at me a minute and says, ‘Lieutenant?’ ...‘Yeah,’ I said back. She said, ‘You’re the coffee lieutenant!’ ...I said, ‘What?!’ ...She says, ‘Your’re the coffee lieutenant!’ ...She calls a couple of the other guys over. They were from Messina New York, which if you look on a map is like a quarter of an inch from Canada. They were rotating in, a couple of weeks at a time. She said to me, ‘The guys from the last rotation were telling us about this ESU lieutenant who would come around, every night, and had us cups of coffee. I thought they were full of shit... but YOU’RE the coffee lieutenant!’”

Well, the coffee lieutenant worked for nearly nine months straight — beginning when he arrived at the scene just hours after the towers fell — until the final day of the recovery effort, running the night shift with another NYPD Lieutenant. Following that, he bounced back over to Narcotics division, but a couple of months later when a handful of ESU Lieutenants retired, Cuneo was called back to ESU.

When he retired from NYPD in 2006, Cuneo stayed ‘on the job’ at a post in which he’s tasked with protecting some of New York’s most vulnerable young people.

Here’s to the Sheepdogs ... the ‘coffee lieutenants.’