Editor’s note: Enjoy this excerpt from “S.W.A.T.: Blue Knights in Black Armor,” a book by Lt. Dan Marcou, ret.. Marcou is a longtime Police1 contributor and author of many law enforcement books. His most recent book, “Law Dogs II: More Great Cops in American History” is a collection of stories of incredible bravery, arduous pursuers, dogged investigators, and epic gun battles long forgotten by history, but worth remembering.

Sir Humphrey lowered his head and removed his black helmet. The sweat stung his eyes as he whispered his prayer, “Dear Lord of Mercy, I fight for my king and my country. I hope I shall survive this battle on this muddy field of Agincourt, but the numbers do not favor us. I hope my actions on this day will tarnish neither my honor nor my soul. Lord, give me the strength to leave this battlefield to once again favor my family with my presence. If this not be your will, give my soul the grace and wings to find a home with you and the saints on this Holy St. Crispin’s Day.”

Humphrey was shaken from his most deep and fervent prayer by shouts, “The king! The king! Long live the king!” Sir Humphrey started to rise from his knee as he raised his head and then abruptly dropped down to his knee again and lowered his head, for his eyes had met King Henry’s. The king sat astride his magnificent horse not five feet from where Sir Humphrey had knelt in prayer. His armor was not the armor of a king but the armor of a warrior leader, who shared the dangers of battle with his army. He shared the hardships of the march, and he had felt the sharpness of the sword and survived.

His armor was the armor of a brother warrior, and his words were the words of an honorable brother knight. His voice was loud and regal. The words stretched out across the battlefield and beyond. They filled each knight and every bowman’s heart.

“My brave soldiers, some of us have seen our last sunrise, ate our last meal, and are about to say our last most sincere prayer, for we are marked to die. This time we all ask ourselves why we must fight and possibly die on this St. Crispin’s Day. Is it for gold? Is it for fine garments or land? I say No! I do not covet any of these.”

“I am covetous of something that can only be found on this battlefield this day. That is the honor of fighting beside each of you. I hope that each of you seek the same honor for when such honor is fought for and won, it overcomes death and outlives life. This honor will be carried by those who survive this day in our hearts and in our minds, and it will be marked on our bodies in the wounds we receive and the scars they become.”

The king’s countenance suddenly changed, and there was a harshness and disgust in his face that showed the words he was about to speak did not come easily, “If there be any among you who wish to secure a long life more than honor and flee from this fight, do so now. I will bid you leave and give you enough crowns and a passport for passage home. Leave now, for we who have stomach for the fight do not wish to die among you.” The king paused and no man moved from his spot.

The king’s face changed once again, and he adjusted his seat in his saddle to stand in his stirrups. He was the embodiment of courage, and all of his soldiers leaned forward as one to hear his words, certain that they would bring courage to them. “Those of us who stay and fight on this day and outlive this day will pause on all future St. Crispin’s Days by drinking ale in memory of those we will leave here on this field of battle. We will stand tall when others mention that we fought here together. All men in your presence will feel small knowing that they were not here and find themselves in the presence of one that was.”

“And the amazing feats of bravery that shall be done on this day will be the grist of lore around campfire and hearth for as long as there is an England. They will speak of the bravery,” the king then made eye contact with each knight as he named them slowly, “of Bedford… Exeter… Warwick… Talbot… Salisbury… and my dear brother Humphrey. What deeds, what great deeds, what great feats you will all perform today that will enable your countrymen that could not be here to say they too are Englishman like those who carried the shield, sword, and longbow at Agincourt.”

As the king’s eyes met Sir Humphrey’s, the good knight knew that his prayers had been answered. He would leave this field in body or in spirit, but either way, he would leave with honor as the brother to a king. Humphrey had never heard such a loud silence. He was in the midst of ten thousand heavily armored men quiet, all straining to see and hear the king. Each man was trying to draw some of his strength to help them make it through this terrible day.

The king then paused to look at his men, his brave men. Those that survived the day would later say, “I was afraid as I have ever been, and then the king looked me straight in the eye. Me! And he told me they would speak of the brave deeds I would do on the battlefield forever, and the fear was washed away like creek scum over a waterfall.” Each man would report the same feeling of courage breathed into them by their beloved king, their beloved brother.

The king continued, his voice booming and then riding on the breeze to every knight, page, archer, and camp follower.

“This story shall the good man teach his son; And Crispin Crispian shall ne’er go by, From this day to the ending of the world, But we in it shall be remember’d; We few, we happy few, we band of brothers; For he to-day that sheds his blood with me Shall be my brother; be he ne’er so vile, This day shall gentle his condition: And gentlemen in England now a-bed Shall think themselves accursed they were not here, And hold their manhoods cheap whiles any speaks That fought with us upon Saint Crispin’s day.”

The silence continued until all at one moment the meaning of every word filled the gentled beating heart of every man on that forever-to-be-remembered field of battle, and at one moment ten thousand men, as if scripted, roared a throaty response, “Brothers! Brothers! Brothers! Brothers!”

The king gently spurred his horse slowly along the line of soldiers, and the chant continued until throats were hoarse and the king had taken his position in the center of the line.

Sir Humphrey turned his face with new courage and determination toward the task at hand. Sir Humphrey was a knight sworn to give his life for his family, his neighbors, his country, and his king. He gave this oath, but today he would fight as a brother beside his brothers.

On this day that would be remembered for all time, October 25, 1415, he was a honorable knight, the brother of a king. He wore his black armor with pride. As he readied to face the fight of his life, he picked up his helmet. Sir Humphrey of Gloucester would survive the day because of King Henry’s words. King Henry would survive the day because of Sir Humphrey’s deeds.

After the echoes of the shouts of these courageous men had faded, Sir Humphrey of Gloucester dropped to his knee one last time before he would stand and fight and whispered his battle prayer, “Thank you, God, for my wife, for my family, and for my life. May I do my best until I am laid to rest. Amen.”

Humphrey set his helmet upon his head and gazed out the visor. He mounted his horse, which was black as Humphrey’s armor. He followed his king on the advance. He marveled at the way Henry’s armor appeared hot white in the morning sun, so sharp was the contrast to Humphrey’s black armor. Both carried a shield with the lion crest. Humphrey’s was black with a red lion, and the king’s was white with a red lion. They rode toward an enemy that appeared to be struggling in the muddy plowed field it had ridden into. Henry shouted, “Forward, my brave men! Let us ride forward to victory!”

Henry hit the line of French knights hard, cutting a swath through them with his sword and courage. Henry and his horse fought as if they were one. Humphrey slashed and cut trying to stay close to his king, but no one could match Henry on this day, in courage and ferocity, fighting as if he were ten, no, twenty knights. Suddenly, Henry’s horse reared backward and fell from a lance thrust deep into the noble steed’s heart. The king stayed with the steed all the way to the ground and somehow dismounted standing, but standing in the midst of knights on horseback is merely a momentary station stop between life and death. The king parried one sharp blow with his sword and another with his shield as the enemy engulfed him, recognizing the opportunity to realize sweet victory with the death of this noble knight-king.

Humphrey slashed, cut, recovered, and slashed his way to his king. When Sir Humphrey reached King Henry, the warrior-monarch was on his back blocking blows with his battered, but intact, shield. The enemy, in their excitement to be the one who killed the king, had lost focus and could not finish the job. Their tunnel vision did not afford them the opportunity to see swift death arrive in the figure of Sir Humphrey, whose armor was as black as the night he was about to send them into.

Humphrey killed each knight close to King Henry with no need for a coup de grâce. Each died after receiving the first blow. Each fell to the ground as dead as Julius Caesar.

Henry made it to his feet after receiving the reprieve offered by Humphrey, and both knights stood back to back and fought all comers holding thusly the advanced ground they had gained until they were joined by the rest of the English army.

Both warriors fought until there was no one left to fight. All who dared challenge them for this piece of ground now lie dead upon it and would soon lie dead under it. The two knights then leaned one against the other, slowly lowered to the ground, and sat exhausted, breathing the air of sweet life in the presence of horrible death. The day was won by this outnumbered band of brothers who did not fight for a country but fought for each other.

The noble knight Exeter rode up to Henry and Humphrey and exalted, “Sire, the day is ours. Your courage gave us all heart, and we have defeated the French in total.” Exeter dismounted, approached, and dropped to a knee stating, “Sire, may I speak?”

“Speak, Exeter,” gasped the king, as he removed his helmet to reveal his hair matted with the sweat and blood earned in the battle. “As I approached the fight that you were engaged in, it appeared as if you were in white armor and then black and then white and then black, and I was so transfixed by this vision I almost could not concentrate on the fight before me. I thought, how could the king’s armor change in color so? What kind of magic was this? Then I saw the truth was there were two of you fighting as one like I have never seen before and feel I shall ne’er be granted the privilege to see again.”

The king looked to Exeter and then looked about the harvest of this day’s work. After a long while he quietly spoke, “Noble Exeter, you give me pause to think. I think you saw what has always been and shall always be. There will always be knights clothed in honor and virtue to protect those who could not breathe free if not for these knights. Some of these knights will have to always be in black armor to wage battle in dark places with dark enemies who do dark deeds to those lambs these knights have sworn to protect. I have seen it in a dream. There will always be a need for knights who will follow us throughout the ages, knights in black armor who fight as one.”

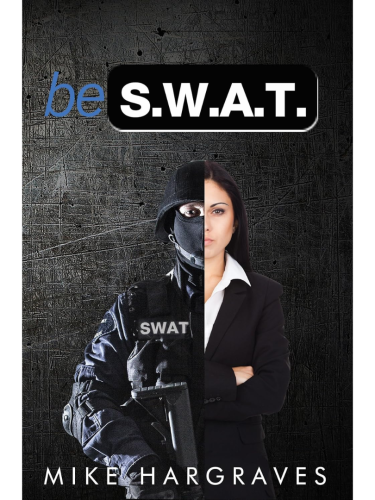

This article, originally published on June 16, 2009, has been updated to update hyperlinks and the book cover image.