By Steve Tracy, P1 Contributor

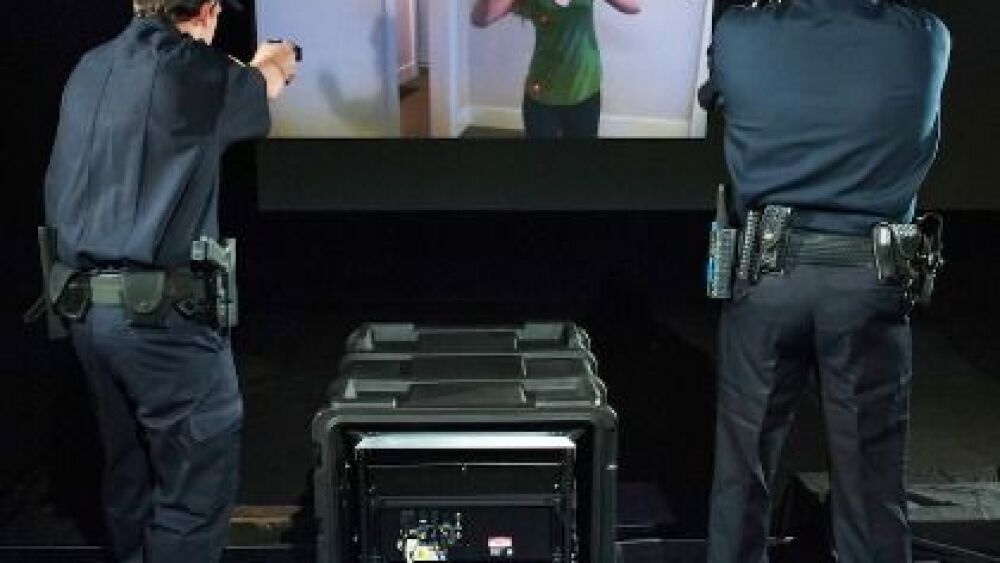

Virtual training systems offer much more than just shoot/don’t shoot scenarios. Simulators offer realistic training that affords two important results. The first is protecting an agency against failure-to-train lawsuits and the second, and most important, is that the training can save officers’ lives.

Today’s police simulators have come a long way over the past three decades (who remembers using laser discs?). Technology has advanced to where systems are more realistic in appearance on screen, scenarios feel more genuine (not as cheesy as those first ones with cops doing the acting), and firearms are more authentic to use.

Training that delivers experience

Certainly simulators offer shoot/don’t shoot scenarios where a subject may draw a gun or a wallet, but their branching options allow the instructor to cause a subject to comply when proper verbal direction is given by an officer to “drop the knife!”

Use of commands emphasizes de-escalation techniques and compliance/non-compliance training provides officers valuable experience. A calm and composed response in a stressful situation allows police officers to have a “been there/done that” sense of accomplishment. Experience is gained through simulations that would otherwise be impossible for uncommon incidents. Officers can run through dozens of various deadly force encounters in an hour’s training that they may otherwise never encounter during an entire career.

Firearms simulators supplement live fire training on a shooting range, but certainly do not replace it. There is a need for ammo down range, but there is also a need to train beyond qualifying and the courts have mandated as much for police agencies.

Training to prevent or break out of tunnel vision

Simulators can enable an officer to experience tunnel vision during scenarios. This is difficult to achieve on a shooting range, but can be a life-saving ability for an officer to identify when this happens and how to adjust response.

While focused on a subject in a simulation scenario, other important occurrences just off to the side often go undetected. Explaining tunnel vision and the need to continue to check to the sides during high stress situations is difficult, but a simulation scenario can demonstrate it to great effect.

A particular scenario caused officers to engage and fire upon a subject shooting from behind a barrier. While the officer fired back, a second subject shot at the officer from another barrier to the right. Most cops never see the second subject due to tunnel vision. Playing back the scenario and then giving the chance for officers to improve their response is an example of how simulators can transform the learning process.

Training to use your gun’s sights

When scenarios happen fast and subjects fire at officers with short warning, officers will often draw and fire without using their sights. Up-close hits may still find their mark, but as a trainer, it is obvious when the officer’s rounds are not hitting as the armed subject will continue to shoot. Trainers see officers realize that their actions are not working and trainers witness officers concentrate on their front sight and then make the hit. Playing back the scenario, officers learn when it is pointed out that firing fast and missing is much worse than using the sights immediately and getting that first hit. Again, what is easy to “show” during simulation training would be difficult to explain on a static firing range.

Marksmanship training

In addition to the judgmental scenarios, many simulators offer marksmanship training. Beyond facsimiles of paper targets that are either static or moving, systems that track muzzle movement can aid in proving trigger control by playing back the muzzle’s movement (low and left when “jerking” the trigger). For officers truly interested in improving their firearms proficiency, these marksmanship portions are invaluable.

Realistic firearms and other tools

Alongside duty handguns, most simulators offer backup/off-duty guns, rifles, shotguns, electronic control devices, batons, sprays, flashlights, and some even involve vehicles driving to a scene and then exiting the squad car. Moving to cover/concealment with most systems is accomplished due to projection systems that are high mounted instead of being situated on the floor. Scuba tank-charged air systems give realistic slide movement on handguns that disrupt the sight picture and the electronics inside the training pistols (which are incapable of firing real ammunition) are easily calibrated to fire a certain number of shots. For example, a 17-shot Glock pistol used for simulation training has a tiny computer that knows if the magazine was removed and will therefore make the pistol capable of 18 shots as if the magazine was topped off with another round.

Single or multiple-screen systems

Almost 360-degree systems promote even greater realism. While these simulators take up more space than simpler single screen systems, their realistic scenarios can amp up an officer’s feeling of being in the middle of a genuine incident. It’s one thing to face a scenario taking place directly in front of you, but when things are happening all around (especially with the possibility of something happening behind you), you see when officers begin taking the training realistically. Officers’ voices rise in volume and pitch when a wraparound system makes them extremely cautious.

Officers should be informed to take the training seriously. Those that do (and even the most jaded soon find themselves immersed in the reality of the situations), find simulator training to be a positive experience. Often trainers will have officers come to them and say that a serious incident was made easier to handle because the officer had already been through it via simulation training.

Serious training

Care should be taken to make sure that there is never an audience (even of fellow officers) when training takes place in order to keep it realistic. People do not take scenarios realistically when they know others are watching.

Some officers will really get into the scenarios and respond with genuine exhibition of stress factors. Police supervisors should not observe subordinates during simulation training. Simulators are designed to allow failure with the ability to perform repeats to improve and overcome. If a supervisor sees an officer fail a scenario, that failure may be remembered years later during a real incident. We cannot have a supervisor make a judgement or assumption and think, “Officer Jones has just been involved in a shooting and I remember when he performed poorly five years ago during simulator training.” The officer may have improved and performed excellently during subsequent simulator training.

Police departments should give serious consideration to obtaining a simulator for training purposes. Most instructor training is included with the purchase of a system and several departments may consider sharing the cost of a system. Smaller departments would most likely train on the system once or twice a year, so it could be shared with neighboring police agencies. Many manufacturers of these simulator training systems provide free grant assistance as well.

An excellent supplement to other training

Virtual training systems are an excellent supplement to standard police training. Live fire range training and classroom instruction on response to resistance are mandatory parts of police instruction. But so much more can be added through the implementation of a virtual training system. Officers find them to be a positive and challenging experience and training they actually look forward to. These advanced virtual training systems are much more than shoot/don’t shoot – they can actually save officers’ lives.

About the Author

Steve Tracy recently retired from the Park Ridge Police Department (which borders the northwest side of Chicago) after 30 years of service, 28 as a firearms instructor.