by Police1.com Columnist Major Steve Ijames

Sponsored by TASER

The National Tactical Officers Association (NTOA) offered its first impact projectile “train the trainer” program in 1995, followed within a few months by the International Association of Chiefs of Police (IACP). At that time, police agencies were clamoring for the so called “new less lethal technology1”, as they struggled to effectively engage an ever increasing number of unconventional adversaries. The situations officers faced were challenging, and generally fit into the following two categories:

- Those affected with mental illness and:

- threatening suicide.

- armed, non-assaultive, ignoring demands to put down their weapon.

- Armed and barricaded subjects, who exited the stronghold and refused to put down their weapons.

Many agencies had experienced the operational pain created by the verbal command/deadly force technology gap and recognized the benefits that an extended range impact device brought to the table. Unfortunately, a significant number of those who were involved failed to anticipate the inherent conflict between conventional firearms marksmanship training and the firearms platform used to deliver impact energy.

The two concepts are “apples and oranges” and as conceptually different from a teaching and policy perspective as the PR-24 and MP5. This point has regretfully been hammered home via numerous operational failures, serious physical injuries, and deaths. As a result, the NTOA and IACP set out to “train the trainers” so primary risk factors such as aiming point could be addressed and the negative outcomes reduced.

Along with the training programs came instructive articles, training keys, and model policies-one of the first in the NTOA journal the Tactical Edge2

. This 1996 piece focused on impact projectile use and the need to balance incapacitation with the potential for causing death or serious physical injury.

Hundreds of classes and magazine articles later, impact projectiles are common place where they once were “new,” and progressive and contemporary police agencies have long been equipping officers with impact rounds to address the unconventional adversary. Some chose this course of action out of a perceived legal obligation to do so. There is no question that civil actions have been and will be filed accusing agencies of failing to deploy “less lethal” options.

In one case,3 a magistrate heavily criticized the agency for failing to train and equip its officers in “alternative, less drastic measures.”

Other courts4 have made it clear that there is no judicial “less lethal” weapons mandate. As such, the vast majority of agencies issuing impact rounds do so not because they fear civil consequences, but because they are committed to doing the right thing — not just for the citizens they serve, but for the officers as well. Most trainers would agree that providing tools that prevent situations from escalating to deadly force are in the best interest of everyone involved-which brings me back to the title and purpose of this article.

Training Paradox

I have been addressing impact rounds from a training, policy, and litigation defense perspective for the past fifteen years. During that time I’ve encountered a variety of impediments to agencies achieving the primary impact projectile mission objective: the resolution of dangerous and challenging police situations with a reduced potential for causing death or serious injury to everyone involved.

Unfortunately, most of these have come to light post event, following a death or serious injury that has placed the agency under the external microscope. Upon close examination, a single training issue — aiming point — has been found at the core of a disproportionate number of the negative outcomes. As such, this issue needs to be addressed once again--and repeated as often as necessary--until the relevent circumstances are fully understood.

Impact rounds are just that: impact rounds. They are designed and intended to be non-penetrating impact devices, and training as it relates to the delivery system, which happens to be a firearm, needs to modified accordingly. The mindset has to shift from a deadly force marksmanship “hit potential” focus to impact device subject control. The crux of this involves changing the concept of where we aim and why.

Hard as it may be for some to understand, we are not “shooting guns” when we deploy an impact projectile; we are “launching night sticks.” That mentality has to guide our aiming process.

It is beyond dispute that “center mass” is the foundation of basic marksmanship training — in situations where officers are facing deadly jeopardy and hitting the target with a penetrating round is the critical task at hand. That is not the situation facing officers when using impact rounds, and the risks inherent in default aiming center mass is in conflict with the primary less lethal mission objective (see definition above). Unfortunately, we have the deaths and serious injuries to prove it.

I’m not suggesting that an officer would never shoot an impact projectile center mass, just that you only do so when the need to stop the behavior justifies the elevated risks involved.

Potential for Death/Serious Injury Based on Target Size

The non-penetrating impact projectile deforms soft body tissue very rapidly. If this deformation is too deep, too fast, or in combination too much of both (viscous criterian5), it can result in serious injury or death. Impacts to the abdominal area displace and deform the internal organs, potentially stretching them to the limit of their elasticity and beyond. This has resulted in critical injuries and one death, and is especially significant when involving the liver, kidneys, or spleen6.

To put this in proper perspective, consider the testing conducted on common impact rounds using Kind and Knox 250A, a 10% gelatin product used by the International Wound Ballistics Association to simulate human tissue. The rounds varied based on mass, velocity, diameter, and material, and the gelatine deformation ranged from two to eight inches. It is important to note that the most commonly used round in American policing routinely displaced five to six inches of the simulated “human tissue.”

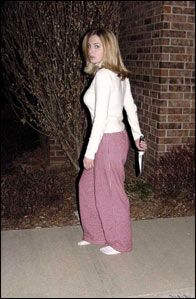

Image 1 |

Keeping that in mind, examine the three photographs attached. Image 1 is a single frame of high speed videography documenting the initial displacement of “tissue,” as an impact round strikes the block of “tissue.”

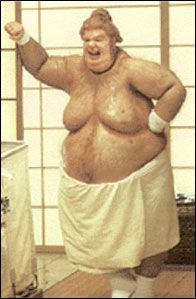

The next two images document “suspects” with dramatically different physical features (below). The first has approximately three inches of body mass (front to back abdominal measurement) available for displacement, while the second has approximately twenty-four inches when measured the same way.

If you follow the “center mass” aiming philosophy, it would be appropriate to target both suspects on the solar plexus/abdomen regardless of the circumstances. Considering what we know about impact round tissue displacement, and the fact that the most common round in American policing will deform the tissue five to six inches, do the suspects face equal risk of internal injury? Not hardly.

Image 2: Three inches of body mass |

Image 3: Twenty-four inches of body mass |

Image 3 The practical reality is the round would grind to a bone jarring halt on the young womans spine, three inches into its five/six inch trajectory-slowed only by the organs that had the misfortune of getting in its way. The same round deployed in the same circumstances on obese suspect #2 would displace less than 1/4th of his available body mass, and do so well above the risk of interaction with the vital organs.

Some might suggest that this “doom and gloom” dissertation makes the aiming point decision remarkably simple — mandate the arms and legs in every situation. That would be fine, if minimizing the potential for suspect injury was the only factor that we considered when facing such tactical interventions. In actuality, impact projectile operators need to consider a number of other relevant factors including:

The abdomen clearly presents an elevated risk, but is also the most likely to result in immediate incapacitation. The abdomen has proven surprisingly durable in actual engagements, having been struck numerous times7 and statistically almost always causing incapacitation with only minor injuries.

Considering this, there is sound logic in teaching operators to direct impact rounds at target areas based on the totality of the circumstances presented (as opposed to a predetermined single aiming point), and a balance between the need to stop suspect behavior and the acceptability of the potential injury outcome. This has resulted in a many progressive agencies using their impact instrument training chart as a general guideline for determining initial aiming points, with the primary focus being on the extremities.

A secondary focus would be on areas such as the lower abdomen and solar plexus, when an escalation of force above primary is necessary and appropriate, and there is recognition of the increased potential for causing death or serious physical injury.

This is a long way from perfect, but reflective of the issues outlined above and geared towards objectively reasonable decision making as it relates to the use of impact projectile force.

1. Firearms deployed extended range impact devices were far from new in 1995, having first been deployed over 110 years before. Extensive 12 gauge bean bag use was documented from 1969-71, including the first fatality.

2. “Less Lethal Projectiles: Seeking a Balance,” The Tactical Edge Magazine, Vol. 14, No. 4, Fall 1996

3. O’Neal v. DeKalb County, Georgia, 850 F .2d 653 (11th Cir. 1988).

4. Plakas v. Drinski, 19 F.3d 1143 (7th Cir.), cert. denied, 115 S. Ct. 81 (1994)

5. Viano, David, C. Ph. D., “Mechanism of Fatal Chest Injury by Baseball Impact.” Clinical Journal of Sport Medicine Vol. 2, No. 3, 1992: 166-169

6. Cuadros, J. H., “A Training Manual for Flexible Baton Selection and Use.” 14 April, 1993

7 Hubbs, Ken. “Less Lethal Munitions are Alive and Well!” (Text and Less Lethal Munitions Database). The Tactical Edge, Winter, 1996: 21-22